I would like to make some comments on the nature of reality that I find highly relevant to the quest for autonomy – not so much in the organisational sense, but of the spiritual kind.

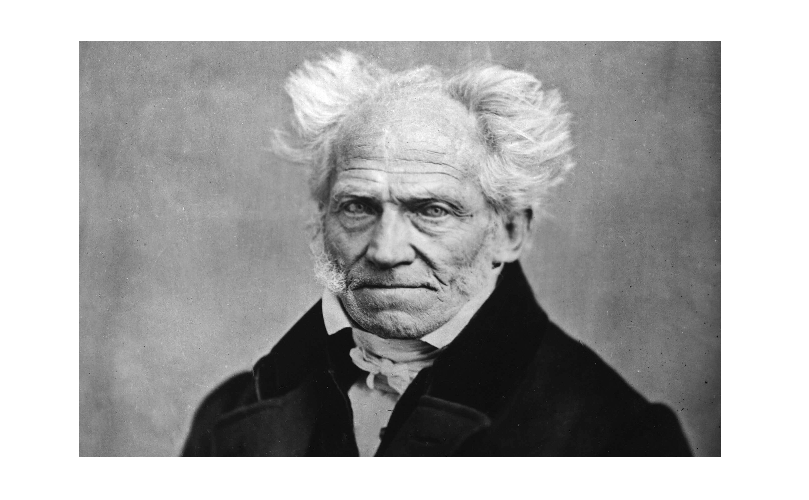

I will make my comments in contrast to Arthur Schopenhauer’s essay “Uber die Freiheit des Menschlichen Willens” (1839) as first translated to English by Konstantin Kolenda in 1960. The essay was an answer to the Norwegian Scientific Society’s prize question “Is it possible to demonstrate human free will from self-consciousness?“, for which Schopenhauer won the prize. The translator Kolenda suggests the essay can be used as an introduction to Schopenhauer’s philosophy in general. I shall begin by summarising the essay’s chapters, and as such provide “an introduction to an introduction” to Schopenhauer’s philosophy.

I – Definition and concepts

1) What is freedom?

Schopenhauer considers freedom a “negative concept” only signifying the absence of any hindrance or restraint. (Your ability to move from A to B can be negated, but you cannot doubly move from A to B.) Schopenhauer finds 3 domains of freedom:

physical freedom – “when actions are not hindered by any physical or material obstacles”

intellectual freedom – “when the medium of the motives—the cognitive faculty—is [not] permanently or temporarily disarranged, or when in an individual case external circumstances [do not] falsify the comprehension of the motives”

moral freedom – “[when not] restrained by mere motives—such as threats, promises, dangers, and the like”

Schopenhauer points out that moral freedom is different from the other freedoms: while a physical object or external circumstance unconditionally hinders you, thus concerns your ability, a motive can never be irresistible in itself and can always be offset by a stronger counter-motive, thus relates to willing. And while the causality of the external world is necessarily so, a free will would have to be a consequence of itself. Schopenhauer postulates that for a human individual to have free will, under given external conditions two diametrically opposed actions must be equally possible.

Schopenhauer also notes that since the will is always in accordance with itself (the will is itself, and not hindered by itself), hence “free in itself”, the problem is not empirical as in the popular concept of “the freedom to do what you want”. The actual question at hand is “Can you will your volitions?”, or simply “Can you will?”.

2) What is self-consciousness?

Schopenhauer immediately writes: “Answer: The consciousness of one’s own self, in contrast to the consciousness of other things; this latter being the cognitive faculty.” Schopenhauer says the cognitive faculty already contains certain forms of the other things that appear in it, and that “these forms are accordingly conditions of the possibility of objective being of things, that is, of their existing for us as objects“. He goes on to say that the cognitive faculty “is directed outward with all its powers and is the scene (indeed, from a deeper point of investigation, the condition) of the real external world. (…) Endless combinations of concepts, brought about with the help of words, constitute thinking. Only after we subtract this, by far the greatest part of our entire consciousness, do we get the self-consciousness.“

The reader may again wonder what Schopenhauer even thinks of as self-consciousness, and the answer comes quickly: “altogether as one who wills. In observing his own self-consciousness everyone will soon be aware that its object is always his own volitions.” Volitions include “desiring, striving, wishing, demanding, longing, hoping, loving, rejoicing, jubilation, and the like, no less than not willing or resisting, all abhorring, fleeing, fearing, being angry, hating, mourning, suffering pains—in short, all emotions and passions.“

Here we find Schopenhauer’s maybe peculiar definition of will, when he writes that the emotions above “enter directly into the self-consciousness as either something which is in accordance with the will or something which opposes it“, referring to alternate wanting and not wanting – constituting the only objective of the self-consciousness – as “manifestations of will” and “movements of the will”.

In other words, Schopenhauer defines will not as one’s conscious volitions, but places it entirely outside of appearance, as that causing the volitions. He has then already answered the question at hand, at least semantically, in defining will as something entirely beyond the self-consciousness and cognitive faculty.

II – The will and the self-consciousness

This chapter deals with the subjective experience of one’s volitions. Schopenhauer clarifies that when you will something, it’s always directed at an objective; there is always something you want to achieve or avoid. The willing therefore always stands in relationship to an objective – there is always a motive.

Schopenhauer points out that alternating motives continuously rise and fall before the self-consciousness, and that these should be regarded as wishes. You can wish two opposing actions, but will only one of them, and the act reveals to your self-consciousness which of the two actions you will do.

A volition is what you will actually attempt to do or avoid. (You may wish to dive into a pool from high altitude, but you learn what you will do as you stand to face the choice.)

You are of course further limited by the world of objects, of what is physically possible. Hence we get something like this model:

Will –> the resolve of a self-conscious volition –> the accomplished objective witnessed in the cognitive faculty

Schopenhauer makes clear that what is being searched for is the origin of the volition — whether it is subject to some rule or whether its emergence is completely lawless.

Schopenhauer says will is man’s authentic self, the true core of his being. That man “is as he wills, and wills as he is“. Schopenhauer therefore warns that the philosophically untrained will always answer the question along the lines of “Yes, I have free will – I can do precisely what I want.” But such statement from the immediate self-consciousness fails to even comprehend the question. The question is not whether you can do what you will, but if you at any time can will the opposite!

Schopenhauer says the self-consciousness alone is incapable of answering the question, and wants to demonstrate the answer through reasoning with the world of objects, where man and his motives also belong.

III – The will and the consciousness of other things

This chapter looks at man as a being in the external world, as we must view others than ourselves, and as we are viewed by others. All changes in the external world are subject to the law of causality, where a change is brought about by a cause, and for this reason necessarily.

Schopenhauer tediously explains how inorganic bodies, plants and animals all respond to causes in their environment, respectively cause in its narrow sense, stimulus, and motivation. In regards to motivation, man is able to abstract general concepts to which he assigns words, in order to keep it in his sensuous consciousness. Motives may then present themselves in our consciousness, alternately and repeatedly, in order to be held up and weighed by the will. Through such deliberation, man is relatively free, compared to the immediate compulsion of the perceptually present objects which act as motives on animals.

However, the ability to deliberate yields in reality nothing but a frequently distressing conflict of motives, which is dominated by indecision and has the whole soul and consciousness of man as its battlefield, and where the decidedly strongest motive drives the others from the field and determines the will. The outcome takes place with complete necessity as the result of the struggle.

Schopenhauer perceptively adds that this battle of motives is a subtle one, including what we would today call “subconscious motives”: “very often a man hides the motives of his action from all others, sometimes even from himself, namely in those instances when he shrinks from knowing what really moves him to do this or that.“

Schopenhauer notes that “only in the very highest, cleverest animals does a noticeable individual character manifest itself, although with the decisive preponderance of the species character.” Schopenhauer says the human character, which is known empirically by the experience of our volitions, is distinctive in every person in that we react differently to motives. He also makes the controversial claim that it is constant and unchangeable from birth throughout life. Schopenhauer sees education opening up new motives to man’s cognition as the only way for our behaviour to change:

“…it is in cognition alone that the sphere and realm of improvement and ennobling is found. The character is unchangeable, and motives operate of necessity; however, they must pass through cognition, which is the medium of the motives. The cognition is capable of the most varied enlargement, of constant correction, in innumerable gradations. That is the goal of all education. The development of reason through information and insights of all kinds is morally important because it provides access for motives to which a man would otherwise remain inaccessible.“

Schopenhauer finishes off the chapter by highlighting the absurd, contrary alternative to the necessity of motives acting upon the will:

“If freedom of the will were presupposed, every human action would be an inexplicable miracle—an effect without a cause.“

“No cause in the world ever brings about its effect all by itself, or produces it out of nothing.“

“In all cases the external causes will necessarily call forth that which is hidden in a being; for this being cannot react otherwise than according to its nature. Here one must be reminded that every existence presupposes an essence, that is, every thing-in-being must be something“

Schopenhauer concludes that everything that happens in the world, from the largest to the smallest, happens necessarily, and just so every action of a man is the necessary product of his character and of the operating motive.

IV – Predecessors

I greatly appreciated this part of the essay, which shows the history of the question of free will in philosophy and theology, thus placing itself in a historical context.

Of the several writers Schopenhauer mentions, he especially commends Joseph Priestley with the words “no writer has presented the necessity of volitions as extensively and convincingly as Priestley in his work exclusively devoted to this subject, The Doctrine of Philosophical Necessity [1777]”. Schopenhauer quotes these passages from Priestley (which are strikingly similar to some of his own arguments):

-There is no absurdity more glaring to my understanding, than the notion of philosophical liberty. —Without a miracle, or the intervention of some foreign cause, no volition or action of any man could have been otherwise, than it has been. —Though an inclination or affection of mind be not gravity, it influences me and acts upon me as certainly and necessarily, as this power does upon a stone. —Saying that the will is self-determined, gives no idea at all, or rather implies an absurdity, viz: that a determination, which is an effect, takes place, without any cause at all. For exclusive of every thing that comes under the denomination of motive, there is really nothing at all left, to produce the determination. Let a man use what words he pleases, he can have no more conception how we can sometimes be determined by motives, and sometimes without any motive, than he can have of a scale being sometimes weighed down by weights, and sometimes by a kind of substance that has no weight at all, which, whatever it be in itself, must, with respect to the scale, be nothing. —In proper philosophical language, the motive ought to be called the proper cause of the action. It is as much so as any thing in nature is the cause of any thing else. —It will never be in our power to choose two things, when all the previous circumstances are the very same.—A man indeed, when he reproaches himself for any particular action in his passed conduct, may fancy that, if he was in the same situation again, he would have acted differently. But this is a mere deception; and if he examines himself strictly, and takes in all circumstances, he may be satisfied that, with the same inward disposition of mind, and with precisely the same view of things, that he had then, and exclusive of all others, that he has acquired by reflection since, he could not have acted otherwise than he did. —In short, there is no choice in the case, but of the doctrine of necessity or absolute nonsense.

It is also well worth sharing Schopenhauer’s quote from Amphitheatrum Aeternae Providentiae (1615), written by Lucilio Vanini, who was later sentenced to death for blasphemy:

The instrument always follows the direction imposed on it by its owner; and since our will in actions is no more than an instrument, while God is the principal agent, it follows that God is responsible for the errors of the will.—Our will depends on God entirely, not only in respect to all its actions but also in respect to its essence. So that there is nothing for which one could hold the will responsible—be it in its action or in its essence—but everything must be imputed to God who has thus created the will and set it in motion.—Since the essence and the activity of will stem from God, all operations of the will, good or bad, must be attributed to him, the will being no more than an instrument in his hands.

Here the most perceptive Vanini follows the absence of free will to its highest conclusion, which lets us ask if we – beyond God as a collective solution to the human condition – are simply trapped in a miserable existence by the creation/existence of this reality.

V – Conclusion and a higher view

When establishing and confirming truth, Schopenhauer recommends a notion from Immanuel Kant, of looking at its grounds alone, and not to its problematic consequences, whence firm points can be used to arrive at higher views that might supersede the convictions that made the initial investigation problematic.

Schopenhauer writes that we feel morally responsible for our character, and that what one calls conscience is really the empirical acquaintance with the nature of our own will. And since responsibility “is the only datum which entitles us to infer moral freedom, freedom must also have the same location, namely, in the character of man“. By such verbal trickery, Schopenhauer declares man to have moral freedom in his essence; our volitions and actions happening necessarily, but always revolving around and adjusting to our will, which is “of course free, but only in itself and outside appearance“.

“…man does at all times only what he wills, and yet he does this necessarily. But this is due to the fact that he already is what he wills.” Schopenhauer teaches us that our behaviour is causal, but reveals in the end that it is really the causal behaviour of a transcendental being with moral freedom (entirely beyond our awareness), thus granting us a higher view where a sense of freedom has been restored!

…although I was impressed with the clarity and subtlety which Schopenhauer discussed the topic of will in previous chapters, I found this chapter to be a sorry part of the essay, one where Schopenhauer wanders away from the prize question to bolster his and Kant’s metaphysical system, which – judging by this essay alone – are verbal constructions and projections without substance.

I will defend above statement and give other critique later on, but this is easier if I first give an independent account of my own existential view.

Bodily Thought (my own view)

Somewhere in my youth I became seriously confused and obsessed about whether there is free will or not, which seemed to me like the most central existential question apart from why anything exists at all. If society is made up of people merely acting out their behaviour through the laws of physics, really having zero say in the matter, that sure seems relevant to just about anything we do! And as it was revealed to me through introspection, there was not a trace of free will in my consciousness. I went on to the internet to discuss this with people allegedly not as sheepish as those in my social environment, but to my surprise people’s reaction was that of a cat being put in front of a mirror – it’s uncertain what really goes on inside the cat’s head, but, beyond a doubt, the cat shows no sign of grasping what is there in front of him. The absence of free will seemed like a secret hiding in plain sight, that people could not see even if I pointed to it. That is how I came to invent “the colour experiment” as a way of coming to grips with the absence of free will. It goes as follows:

Close your eyes, imagine darkness, and then think of a colour.

End of experiment. The accompanying explanation is that a colour suddenly filling the darkness of your mind is maybe the most immediate and vivid choice you can make. Monitoring yourself choosing between different physical actions is too complicated, allowing you to inject silly ideas about what happened. Even a choice between two colours is at first too complicated. To first grasp the idea, there must be no space between your mind not having chosen, and your mind having chosen. Now, what people will find through introspection, depending on their perceptiveness and sincerity, is that the appearing of a certain colour happens arbitrarily!

For someone new to the idea, this will take some time to sink in (as it also took for me), but as opposed to the confusion of a cat, the human mind can be aided with these meditations:

* when choosing a colour, did you turn into the synapses of your brain and rearrange them so they would present your mind with a certain colour?

* were you aware of the colour of your choosing before you became aware of it?

* how does a colour look before you become aware of it?

From here you can be led up an enlightening alley. Cause once you understand how a singular colour appear impulsively – appearing at the moment it appears – you may expand this revelation to witness how all forms of thought similarly appear. Not only is the experience of a colour appearing as it is experienced, but anything ever experienced is appearing as it is being experienced. You notice and realise how absolutely everything that can be experienced is of course appearing thoughts. A colour is an appearing thought. A concept is an appearing thought. A house is the appearing thought of a house. A person is the appearing thought of a person. Finally you understand that “you” are the appearing thoughts of “yourself”. You may find no other “you” than precisely those thoughts that appear about “yourself”. For all that exists is thought.

Now the absence of free will can be emboldened through a different route: when all ideas of yourself are thoughts appearing as they appear, then there is no one around to exercise free will. (The thought of being someone is itself a thought, and not an actual reality. It is impossible to be a cell, be a brain, or be a person.)

Further more, every thought has the property of what can be called sensoric or physiological sensations, what we might call bodily thought. Even happiness and depression are different breathing patterns, pressure, temperature, vibrations and other physiological sensations. Once you try to look closer at what “the emotions of happiness” or “the emotions of depression” are, you will find that the illusion shatters into a myriad of bodily sensations, that can be mapped out proportional to the power of perception applied. Any experience is represented through bodily thought. (What you can here discover personally, has to a large degree already been discovered collectively through our language, as in saying you have “warm feelings” for someone).

We may assume this is because thought and matter are two sides of the same coin. Although our thinking is all we know, most of our thinking consists of observing a world following consistent patterns, which we abstract as the external world of matter (which includes the patterns of our body). And in this “external abstraction”, we find activity in the human body – especially the brain – that run parallel to our thinking. We also know many ways to actively and physically alter our thinking. The best assessment is therefore that we are observing the dynamics of our own thinking. That our thinking is bodily.

Of course, some very impoverished individuals will instead state that there is “only matter”, which begs the question of how they can even think that. Other confused individuals believe that an advanced configuration of matter is what creates thought, as if thought suddenly pops into existence when higher animals develop, which begs the question of how thinking could have ever evolved in the first place, why it would ever be necessary, and why our thinking is so amazingly vivid. No, the only logical explanation is that matter is thought, or rather a description of some dynamics of thought. When we are describing matter, we are reviewing how thought works.

The above does not make sense if you don’t understand what matter is, or rather what it is not. Cause the matter described by physics is in fact not “physical”. If we describe matter in its “smallest components”, then we must describe it as wave patterns. No round atoms or electrons, like in our visual models, really exists, and our best attempt at describing atoms are as bundles of wave energy. So if you break down what a dog is in this fashion, then you may describe a dog as some kinds of vibrations in different frequencies (per second). What does that even mean? What are we even talking about when we describe something as electromagnetic waves? What is a second? What is time? …as you should realise, we do not know what matter is, ontologically.

However, we may describe both matter and thoughts as patterns, and seemingly as the same pattern. We ask “how can matter create thought?”, not contemplating that we invented this separation in the first place. Why can it not be just one phenomenon? I think it is fair to assume that our bodily thinking and the bodies we think of are the same thing. I do not claim this explains much of anything, but I find that it is a more coherent perspective.

Critique of Schopenhauer’s philosophy

Believing that various thoughts are independent, external objects.

Having established my own view of reality as the appearing of thoughts, I can now go on to criticise Schopenhauer for a major blunder that he shares with several great philosophers, in projecting their own thoughts as real and independent objects. I’d like to start with Descartes’ famous statement about the only certain knowledge:

“je pense, donc je suis“

or “cogito, ergo sum” (cogito is Latin for “I think”, not “thinking”)

or “I think, therefore I am“

Upon searching for Descartes’ original French phrase on Wikipedia, I found that Nietzsche was as annoyed with Descartes’ statement as myself:

Friedrich Nietzsche criticized the phrase in that it presupposes that there is an “I”, that there is such an activity as “thinking”, and that “I” know what “thinking” is. He suggested a more appropriate phrase would be “it thinks” wherein the “it” could be an impersonal subject as in the sentence “It is raining.”

I agree with Nietzsche on the false presupposition of the “I”, but I would correct the statement to “thought, therefore existence”, where “thought” is a referral to itself without claiming to understand what it is ontologically, either generally or specifically. So, if we assume a reality greater than that immediately experienced, and somehow responsible for our experience, the model becomes

? –> thought

Although Descartes tried his best to let go of his assumptions, his belief in the ego and how it relates to thinking remained. And this is also the fundamental mistake of Schopenhauer, in juggling concepts like “cognitive faculty” and “character” thinking he has clearly understood what it is, for instance when he firmly believes that the character it a constant and unchangeable object.

Schopenhauer does masterfully explain the absence of free will, but creates problems when he tries to fill the vacuum of a willor. Because he insists someone is willing our behaviour, he must invent a transcendental being just outside of appearance as the true essence of man. This does not allow for how we have come to scientifically explain our behaviour, as the emergent, evolutionary patterns of reproducing molecules.

When the illusion of “free will” is dissolved, the cleanest solution is to discard the concept of “will”, but Schopenhauer keeps it around, despite having insinuated that it is synonymous with volitions:

“Can you also will your volitions?”, as if a volition depended on another volition which lay behind it.”

So he arrives at this model:

the volitions of a transcendental being –> our self-conscious volitions sorting themselves out accordingly

But what is entirely outside of our experience is unknown – a question mark. You can give it any mystical name you like, but it is not necessarily helpful:

Will –> self-conscious volitions

God –> self-conscious volitions

Transcendental being –> self-conscious volitions

Thing-in-itself –> self-conscious volitions

Simulation –> self-conscious volitions

Dream –> self-conscious volitions

Sticking to the concept “will” is very suggestive language, and makes people project dynamics into realities that we do not know is there. A cleaner and simpler model for a greater reality, in line with the principle of solipsism (that thinking is all that is known), is just this:

? –> thought (among it “self-conscious volitions”)

And today we assess, through abstraction of our scientific observations, this situation:

patterns of matter –> patterns of thought

“pattern” here refers to a universal and predictable causality guiding the unfolding of reality. But science has long neglected the glaring omnipresence of thought, and has not quite arrived at what seems to me like the natural hypothesis:

patterns of matter = patterns of thought

Exploring how the patterns of nature unfold can be a very fascinating and rewarding experience for our human minds. It is well to be content with that, and admit we are not clever enough to understand what reality is ultimately. I therefore resent what Schopenhauer seems to have half tried to do 200 years ago – create a complete metaphysical system, a religious philosophy.

A determined character versus increasing personal freedom.

As mentioned above, Schopenhauer claims the human character is constant and unchangeable from birth throughout life. This view seems mirrored in a combination of Hellenistic virtues and Newtonian absolutes, bestowing each person with a limited set of eternal virtues.

If we compare the claim to modern science, then it is correct in that the basic programming of our genes remain the same, but it is still incorrect considering the plasticity of the brain documented by neuroscience, the potentiality of gene expressions pointed to by epigenetics, or how the study of psychology suggests our environment affects us. We should of course be forgiving of the time the essay was written, but we can also blame the attitude of the author. Schopenhauer does not come across as probing or curious, but is rather declaring his absolutes to the unenlightened reader. For instance, he writes with stupid certainty “In its basic features character is even hereditary, but only on the father’s side, while intelligence is inherited from the mother.”

Since Schopenhauer has already decided that character is “inborn and unchangeable”, this creates philosophical problems that must be explained more creatively. A good example is in how Schopenhauer discusses the role of education (as quoted before):

“…it is in cognition alone that the sphere and realm of improvement and ennobling is found. The character is unchangeable, and motives operate of necessity; however, they must pass through cognition, which is the medium of the motives. The cognition is capable of the most varied enlargement, of constant correction, in innumerable gradations. That is the goal of all education. The development of reason through information and insights of all kinds is morally important because it provides access for motives to which a man would otherwise remain inaccessible.”

What Schopenhauer writes about education is interesting and half-true, but let us remind ourselves that we are talking about “brain activity”/thought. The only realm that exists is our thinking itself, while we think the patterns we identify as body and brain underlays our thinking. Whereas Schopenhauer projects an independent object called character, and another independent object called cognition, and describes their interrelation as if the thing motives passes through a tube from the character to the sphere of cognition. But according to science, our motives are responses passed down by evolution, which together form what we experience as the character – we have no grounds to assume a hidden ego responsible for the manifested ego. It is therefore truer to say that our character is a product of cognition rather than preceding cognition, and that various education may develop the manifested character. This is an impossible conclusion in Schopenhauer’s philosophy, since he has declared the character as an absolute and unchanging object. He must therefore explain education as something like the removal of intellectual hindrance for the freedom of the character’s motives.

But isn’t the same character consistently manifested by our biology, such that if only we swap the word “character” with the word “biology”, then Schopenhauer’s philosophy makes sense after all? I would like to address this question starting with a quote from Schopenhauer on Christianity, which he also discards to pave the way for his unchangeable character:

When we consider in addition the Christian virtue of love, caritas—which is absent in Aristotle and in all ancients—the matter is no different. How could the untiring goodness of one man and the incorrigible, deeply rooted wickedness of another—say the character of the Antonines, Hadrian, or Titus on the one hand, and that of Caligula, Nero, or Domitian on the other—alight upon them from the outside, be the work of accidental circumstances, or of mere knowledge and teaching?

Well, Christianity is not a chore; its purpose is to model the spirit of Christ, which models altruism, only found by genuinely seeking answers to questions such as “What would God want me to do?” or “What is good for all of us?”. Jesus was “the son of God” in that he was a supreme example of this “holy spirit”. It is a loving and healing spirit, and we can tell that Jesus possessed it by the numerous tales of him healing the people around him through his presence and words.

Instead of “spirit”, let’s use the concept “mind” to refer to the extent of our thoughts. I do not claim to understand what a mind is (the mind is so sophisticated it has yet to understand itself), but I can say that once upon a time when I was deeply influenced by Christianity, it changed my mind and how I perceived and projected the world around me. It changed my motives and manifested character. I later rejected the Christian identity, and embraced a Norse identity. This again changed my motives and manifested character. So which is my real character? And have I even found my real character? These are strange and difficult questions, and maybe erroneous. Considering the environment I was brought up in, it is easier to explain my Christian and Norse identities as those being natural for me to adopt.

My personal experience is just one way of highlighting how I think we must understand ourselves. As quite similar humans born into a varied set of cultures and circumstances. Upon conception, our genetic programming does not know which environments it will be thrown into, so it has to offer a very large potential that encompasses all the possibilities that our ancestors endured. This includes to understand and navigate the social world, which means you must be able to vividly think like the most intelligent animals on the planet – other humans. In conclusion, everyone is born with a large repertoire of characters, where information from your environment triggers you to act out specific ones.

There are of course people who are pathologically very different, like psychopaths. And not only they, but everyone is different from each other, from the outset and onward. But my point, and critique of Schopenhauer, is that people are in themselves different. Life will reveal what ideologies and relationships float your way, which will change how you perceive and project the world, and how you behave.

To suggest that man is born with one distinct character, and that he can only display this one character throughout life, is laughable with what we today know of our nature. However, if we are flexible and interpret Schopenhauer’s claim of a determined character as “constant at any given moment”, then there is less issue. Causality needs time to change the momentary character.

–I found Schopenhauer’s essay worth reading solely for his notion of freedom as a “negative concept” that only signifies the absence of physical, intellectual or moral hindrance. It is a very helpful, higher concept. Yet I disagree with it. I think that freedom can easily be called a “positive concept”, as well.

Improving one’s health and intelligence makes one abler to do things. A child is better able to learn than when he grows older; an adult is better able to manoeuvre the world than when he was younger. Learning to play a musical instrument or to speak a new language, affects freedom not just in seen options, but in personal ability. Schopenhauer, stuck in his quagmire of the unchangeable character, regards intellectual freedom as “not being cognitively disarranged”, but still admits that humans have more freedom than animals. Since he agrees that humans have more freedom than animals because of our abilities, then he should agree that improving the abilities of an individual increases his freedom!

Since our intelligence is plastic and can be augmented, freedom can also be described as “a positive concept”. And on the advent of artificial superintelligence, we can only ponder the immense freedom of thought that human intelligence may be about to witness. Of course, due to the absence of free will, we can but stumble along this experience as it unfolds.

–If you happened to read through and contemplate this piece, you might now have more options of how to respond to situations, from becoming acutely aware of your bodily thoughts. This can yield an intimate level of freedom from responding to mundane motivations.

There is surely a lot of suffering and injustice in the world, and we may feel justified to “blow it up”. But all representations eventually fade, and a new river of light will eventually trickle your way. I hope by writing this piece, I have helped another person and myself, to forgive the world for its errors and forgive our own reactions to it.